Environmental Movement

History is marked by movements that challenge the dominant political ideology in ways that cannot go unnoticed. Civil rights, women's rights—such movements are often rooted in small beginnings, the passion of few, which becomes the cause of many. Born from late-nineteenth-century concern over resource exploitation, the environmental movement has become an overarching term for the growing public interest in protecting Earth and its natural resources.

Naturalists like John Muir, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and forester Aldo Leopold, in the 1930s and 1940s, invested their time and spirit extolling the virtues of the U.S. wilderness. Both men shared a common vision for protecting the dynamic landscape of mountains and grasslands that was a distinguishing characteristic of the United States. The ensuing battles over damming rivers and logging forests helped shape the modern environmental ethic.

A Crusade for Reform

As the nation grew, the gap between people and the natural environment was widening. The introduction of railroads, telegraphs, and stockyards, helped transform cities into major industrial centers. Populations within cities increased, as immigrants flocked to them seeking employment. The resulting noise, grit, and industrial waste compelled women in the cities to take action. In Chicago, social worker Jane Addams was prepared to do just that. Coupled with the efforts of Alice Hamilton and Mary McDowell, Hull House was formed in 1888.

The creation of Hull House helped mark what is known as the Settlement House era. Across the United States, settlement houses sought to reform communities by raising public awareness about problems to find resolutions. Working-class neighborhoods were in the most dire straits, with overcrowding and poor sanitation. Hull House was concerned with the need for solid waste and sewage management in poor working neighborhoods. To remedy this, Addams became trash inspector for her Chicago ward. Likewise, McDowell motivated people to consider reduction, and pressured industries to take responsibility for their trash and sewage disposal.

The crusade for reforming working-class neighborhoods continued as McDowell opened a new settlement house in the meat-packing section of Chicago. Between the polluted waters of the Chicago River and the fields of slaughterhouse waste, McDowell began to make a strong connection between the conditions of work and daily life. Most people working in the industrial sections of the city couldn't afford to live anywhere else. Industrial byproducts that contaminated the city's air and water were unregulated, and industries weren't compelled to address the problem. Under Teddy Roosevelt, reformers

An Age of Abundance

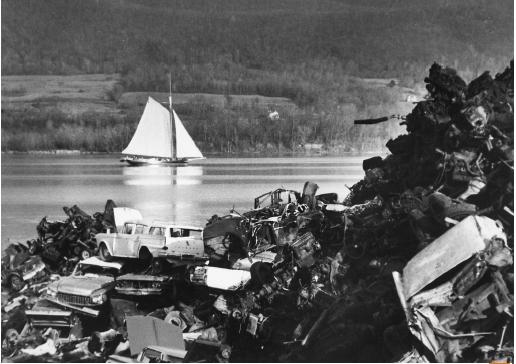

At the end of World War II, the United States underwent rapid economic growth. The postwar abundance could be easily pinpointed by the mass consumption of everything from energy and detergents to plastics and pesticides. Goods were created and marketed to provide convenience, and amenities were plentiful. As Samuel Hays observed, a "greater distance between consumption and its environmental consequences increasingly depersonalized the links between the two" (Hays, p. 16). If people couldn't see an immediate environmental impact, society could ignore it.

The postwar impact on the environment was difficult to ignore. Within ten years, three major bouts of air pollution paralyzed the United States and Europe. In 1943 a thick smog trapped residents of Los Angeles in an unhealthy shroud of air pollution that came to be known as Black Monday. Five years later, in the Pennsylvania town of Donora, another deadly smog hung over the Monongahela Valley leaving six thousand people ill and twenty dead. In perhaps the worst case of air pollution, a deadly fog descended on London in 1952, killing several thousand. Yet in spite of these and other environmental problems, the general public and policymakers remained relatively unconcerned.

What did finally awaken the public was the growth of an antinuclear movement in the early 1950s. As the United States performed aboveground testing of nuclear weapons, the implications for human life were startling. Protest efforts in neighboring Great Britain and the aftermath of Bikini Atoll created widespread fear about the risk of radioactive fallout from nuclear testing. Housewives and high school and college students mobilized against testing, and communities protested. Everyone, it seemed, had a stake in the debate.

The Power of Activism

By the time the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union was signed in 1963, citizens were learning about chemical fallout right in their own backyards. In 1962 Rachel Carson's Silent Spring introduced a public dialogue about the impacts of toxic chemicals, specifically DDT, on wildlife and the environment. César E. Chávez, leader of the United Farm Worker's Union, raised awareness of the diseases farmworkers suffered due to chemical exposure. Eventually farmworkers were able to use public awareness as a bargaining tool in their work contracts, calling for a national boycott on grapes.

Carson, like the reformers before her, felt an explicit need to make information accessible to the public, and many other scientists agreed. Paul Ehrlich's Population Bomb, published in 1968, sounded the alarm about over-population and the environmental damage that would inevitably result from a population too large for Earth to support. Garrett Hardin's "The Tragedy of the Commons," also published in 1968, explored the concept of the environment as a common area, subject to misuse in the absence of regulation. The proliferation of publications and community protests sent the message to state and national government that the pollution problem needed to appear on their agendas.

Environmental issues were swept up in a time of great social unrest. Marked by counterculture ethics and the tool of protest, citizen groups began to make connections between technological progress and pollution. Traditional wilderness preservation environmental groups dating back to the turn of the twentieth century, like the Sierra Club and the National Audubon Society, were now working alongside a new breed of antipollution activists. Protesters considered quality-of-life issues to be environmental issues. If the industries supporting their lifestyles were also degrading their neighborhoods, change needed to occur. Among the organic farms, counterculture communes, and underground publications, society was seeking to reestablish a connection with the environment.

The New National Agenda

If the 1960s arrived with a compelling or infamous start, it exited in the same fashion. In 1967 an oil tanker off of Great Britain ran aground, spilling 40,000 tons of oil. Attempts to contain the accident and salvage the remaining oil were useless. The tanker spilled another 77,000 tons of oil that washed

In 1969, in response to the public's demand for action after the Storm King case on the Hudson River, President Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). With NEPA, the national government was taking a stand for the first time to integrate public concerns into the national environmental agenda. NEPA gave the national government the responsibility to help eliminate environmental destruction and seek a balance between the needs of industry and the environment. The Council on Environmental Quality was created to help advance this cause.

The 1970s are noted by many as the doomsday decade. Nixon's enactment of NEPA was a first step. Interest in environmental issues had remained strong from the debate over nuclear testing in the 1950s to the uninhibited use of DDT and the devastating effects of pollution on aquatic ecosystems. Environmental issues had been tied into larger social movements, but as the United States moved into a new decade, concern for the environment became a stand-alone issue. Urban pollution issues, both air and water, were tied into social interests/human health before gaining acknowledgement as purely environmental issues that had consequences for life other than humans. The intrinsic value of nature, with the exception of the wilderness preservation movement at the turn of the twentieth century, was not truly addressed until this time.

The Advent of Pollution Policies

The public's environmental agenda and steady pressure to create national pollution laws led U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson to make a bold move. He had an idea for a national teach-in on environmental issues. A task force calling itself Environmental Action was formed to develop the idea. By seeking official support, avoiding confrontation, and scattering events across the United States, the committee hoped to involve the entire society. Many established environmental groups refused to participate, cautious of the activism that typified the era. Many of the older environmental organizations worked from a much more traditional standpoint—within political and social parameters. They believed the extremism of groups like EarthFirst! and Greenpeace threatened the progress they had made thus far and would alienate mainstream public support. Despite their hesitancy, the day met with great success. In the end, more than twenty million Americans participated in the nation's first Earth Day events on April 22, 1970.

Shortly after the Earth Day celebration demonstrated public concern about environmental problems, Barry Commoner, a notable scientist and professor, published The Closing Circle: Nature, Man, and Technology. Commoner wrote about the need for humans to return to a state of equilibrium with nature.

Citizen action groups like the Group Against Smog and Pollution (GASP) and the Campaign Against Pollution (CAP) lobbied their local governments for change. In Pittsburgh, GASP activists brought attention to pollution by selling cans of clean air and opening their own complaint department. The League of Conservation Voters published lists of top-polluting industries and rated politicians based on their environmental voting record.

The national government responded and took steps towards regaining the balance discussed by Commoner and those before him. The existing Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act were amended to better address the causes and effects of pollution, and regulatory measures were put into place. Between 1972 and 1976, several new federal acts were also passed, regulating ocean dumping, pesticides, and the transportation of waste. The pressure of local groups, acting independently of larger mainstream groups, paid off. Several pieces of environmental legislation were passed, addressing the transportation and cleanup of chemicals and waste.

Legal Support for Environmentalists

Special-tactic groups began to emerge to accommodate the transition of environmental issues onto the national agenda. One such group was the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). A generous grant from the Ford Company led to the creation of the NRDC, a science-based initiative dealing with the new legal aspects of the movement. Even local citizen groups began to focus their interests. The Brookhaven Town Natural Resources Committee (BTNRC), a coalition of scientists and residents of Long Island, New York, was a leading antipollution group. Compelled to push for the litigation of chemical use, especially pesticides, they reestablished themselves as the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). Throughout the 1970s the EDF, also with the help of Ford, gained notoriety for its success in waging the war on pollution in court.

The legal and scientific services offered by groups like the NRDC and EDF became important assets to the environmental movement during the 1970s. From 1976 to 1978, communities were finding themselves more widely exposed to pollution than they had first realized. Hazardous chemicals were being dumped in Virginia, the Hudson River was heavily contaminated with PCBs, and cows in upper Michigan were poisoned by polybrominated biphenyls (PBB). In Love Canal, New York, where many homes had been built on a chemical waste dump, Lois Gibbs worked endlessly to rectify the situation, lobbying polluters, politicians, and attorneys for support. In 1978 President Jimmy Carter declared a state of emergency. Gibbs later formed the Citizens Clearinghouse for Hazardous Wastes (CCHW), which helped other communities with toxic waste problems, while calling for greater toxics controls. Love Canal led directly to the passage of the Superfund law.

The International Movement

Europeans were struggling with their own environmental disasters. Swedish scientists had been studying the connection between common air pollutants like sulfur and nitrogen dioxides and high levels of acidity in many of their waters. Documenting an overall decline in the biological diversity of Scandinavia, the scientists hoped to capture international attention. The 1972 U.N. Conference on the Human Environment, hosted by Sweden, was the perfect place to present their findings. Air pollutants transported by precipitation and deposited across the land came to be known as acid rain. The idea that pollution did not remain a local problem but could be carried long distances alarmed the international community. By 1979 thirty-five countries signed the first international air-pollution agreement, the Geneva Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution.

During the course of the 1970s, the face of environmentalism had shifted to civil action. Just as it seemed that environmental policies were effectively in place, the political climate was about to make a complete turn—but not before the fear of nuclear power reared its head again. In 1978 a partial meltdown at the nuclear plant in Three Mile Island, Pennsylvania, generated a ripple of fear and uncertainty throughout the public. Residents were evacuated, and radiation-contaminated water was released in the nearby Susquehanna

![Aview of earth from space. (United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration [NASA].)](../images/paz_01_img0099.jpg)

A Renewed Sense of Commitment

Environmentalists were rallying for more stringent enforcement of environmental policies, but the Reagan administration failed to express the same level of enthusiasm and support that had characterized the Nixon and Carter presidencies. Economic and political decisions that once involved environmental organizations now seemed to undermine the very spirit and intent of NEPA by sidelining environmental efforts. The membership ranks of environmental groups grew in response to these political threats, and a new environmental agenda focused on acid rain, ozone depletion, and global warming.

Without the willing support of the national government, environmental groups began to take matters into their own hands. Organizations like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, which had always encouraged direct action, had an ally with the radical Earth First!, which used similar tactics. Often referred to as direct-action groups, their methods embraced the prevention of nuclear testing, whaling, and logging through physical means. Their actions met with mixed reviews. Some felt that the movement had out-grown this type of action and that such efforts undermined the legislative progress that had been established. But activists felt that national legislation was being relied on too heavily to provide all the answers. Reintroducing the activism of the earlier movement seemed to be one of the few methods that educated the public about hazards of pollution and kept the debate alive.

With greater access to information, increasing numbers of antitoxics groups, and pressure from the international community, the pollution problem was not going to disappear. An incident in Bhopal, India, in 1984 prompted much debate about the need for uniform environmental standards and it brought a dire problem into the spotlight that had for years been ignored: environmental injustice. In Bhopal over 2,000 people died and nearly 250,000 others suffered lung and eye damage when a poorly maintained chemical storage tank overheated. The Union Carbide Company, which operated the plant internationally, was not abiding by the same regulations that applied to its West Virginia branch. The accident echoed eerily of the Gauley Bridge deaths in the late 1920s, when Union Carbide knowingly exposed hundreds of African-American miners to dangerous silica deposits.

The environmental movement expanded throughout the 1990s, becoming more international in its efforts. In 1992 the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro was attended by over 142 heads of state. Environmental organizations joined the proceedings with hopes of influencing the outcome. Five years later, organizations reconvened to assess the progress that had been made since the Earth Summit. Bound by the underlying desire to improve the environment, grassroots actions, national organizations, and legal proceedings have combined to present a positive force for change. NGOs were excluded from the 1992 Earth Summit. A satellite conference was established instead. The result was that the NGOs drafted their own alternative plans, put together daily news on their conference and delivered it to the hotels of those attending the main conference, and essentially—not much was truly accomplished at the first Earth Summit. However, the satellite conference put NGOs on the board as the key players in the environmental movement. They were perceived as more knowledgeable and could network more easily in the absence of red tape that government parties encountered.

The movement represents an amalgamation of issues, from species protection and land conservation to pollution. It has also propelled itself by employing a variety of tactics to attract attention, from petitions and protests to publications and organizations. The prospect of danger to human life in the form of pollutants has motivated people from all classes and walks of life to engage in the movement to improve the quality of life. The ability to relate the causes of pollution back to human industry gave communities a sense of empowerment. Witnessing the perils of pollution in several different forms, the public has been moved to respond. The issue of pollution has compelled nations to consider the wider implications of their decisions and actions. It has shaped the course of the environmental movement, as the realization has grown that the environment extends beyond a county sign or a border patrol—and that the issue of pollution is about the shared responsibilities of consumers, manufacturers, and all residents of the larger, global community.

SEE ALSO A CTIVISM ; A DDAMS , J ANE ; A GENDA 21 ; A NTINUCLEAR M OVEMENT ; B ROWER , D AVID ; C ARSON , R ACHEL ; C HÁVEZ , C ÉSAR E. ; C ITIZEN S UITS ; C OMMONER , B ARRY ; C OMPREHENSIVE E NVIRONMENTAL R ESPONSE , C OMPENSATION, AND L IABILITY A CT (CERCLA) ; D IOXIN ; D ISASTERS : C HEMICAL A CCIDENTS AND S PILLS ; D ISASTERS : E NVIRONMENTAL M INING A CCIDENTS ; D ISASTERS : N ATURAL ; D ISASTERS : N UCLEAR A CCIDENTS ; D ISASTERS : O IL S PILLS ; D IOXIN ; D ONORA , P ENNSYLVANIA ; E ARTH D AY ; E ARTH F IRST ! ; E ARTH S UMMIT ; E HRLICH , P AUL ; E NVIRONMENTAL R ACISM ; G AULEY B RIDGE , W EST V IRGINIA ; G IBBS , L OIS ; G OVERNMENT ; G REEN P ARTY ; G REENPEACE ; H AMILTON , A LICE ; L A D UKE , W INONA ; N ADER , R ALPH ; N ATIONAL E NVIRONMENTAL P OLICY A CT (NEPA) ; N ATIONAL T OXICS C AMPAIGN ; N EW L EFT ; P OLITICS ; P RESIDENT'S C OUNCIL ON E NVIRONMENTAL Q UALITY ; P ROGRESSIVE M OVEMENT ; P ROPERTY R IGHTS M OVEMENT ; P UBLIC I NTEREST R ESEARCH G ROUPS (PIRGs) ; P UBLIC P ARTICIPATION ; P UBLIC P OLICY D ECISION M AKING ; R IGHT TO K NOW ; S ETTLEMENT H OUSE M OVEMENT ; S MART G ROWTH ; S NOW , J OHN ; T IMES B EACH , M ISSOURI ; T RAGEDY OF THE C OMMONS ; T REATIES AND C ONFERENCES ; U NION OF C ONCERNED S CIENTISTS ; W ISE U SE M OVEMENT ; Z ERO P OPULATION G ROWTH .

Bibliography

Allen, Thomas B. (1987). Guardian of the Wild: The Story of the National Wildlife Federation, 1936–1986. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Brandon, Ruth. (1987). The Burning Question: The Anti-Nuclear Movement Since 1945. London: Heinemann.

Buck, Susan J. (1991). Understanding Environmental Administration and Law. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Carson, Rachel. (1962). Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Chiras, Daniel D. (1991). Environmental Science. Redwood City, CA: Benjamin/Cummings.

Commoner, Barry. (1971). The Closing Circle: Nature, Man, and Technology. New York: Knopf.

de Steiguer, J. E. (1997). The Age of Environmentalism. New York: McGraw-Hill.

de Villiers, Marq. (2000). Water. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Ehrlich, Paul. (1968). The Population Bomb. New York: Ballantine Books.

Gottlieb, Robert. (1993). Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Gottlieb, Robert. (2001). Environmentalism Unbound. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Grossman, Mark. (1994). The ABC-CLIO Companion to the Environmental Movement. San Francisco: ABC-CLIO.

Guha, Ramachandra. (2000). Environmentalism: A Global History. New York: Longman.

Hardin, Garrett. (1968). "The Tragedy of the Commons." In Science 162:1243–1248.

Hays, Samuel P. (2000). A History of Environmental Politics Since 1945. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Kline, Benjamin. (1997). First along the River. San Francisco: Acada Books.

Markham, Adam. (1994). A Brief History of Pollution. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Nash, Roderick. (1982). Wilderness and the American Mind. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Nicholson, Max. (1987). The New Environmental Age. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Papadakis, Elim. (1998). Historical Dictionary of the Green Movement. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Rubin, Charles. (1994). The Green Crusade. New York: Macmillan.

Willets, Peter. (1982). Pressure Groups in the Global System. London: St. Martin's Press.

Other Resources

Citizen's Campaign. "Coalitions and Affiliations." Available from http://www.citizenscampaign.org .

Environmental Defense Fund. "Notable Victories." Available from http://www.environmentaldefense.org .

Natural Resources Defense Council. "Environmental Legislation." Available from http://www.nrdc.org .

United Nations. (1997). "UN Conference on Environment and Development (1992)." Available from http://www.un.org/geninfo/bp/enviro.html .

Worldwatch Institute. "WTO Confrontation Shows Growing Power of Activist Groups." Available from http://www.worldwatch.org .

Christine M. Whitney

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: