Popular Culture

Popular culture can be thought of as a composite of all the values, ideas, symbols, material goods, processes, and understandings that arise from mass media, such as the advertising and entertainment industries, as well as from other avenues, such as games, food, music, shopping, and other daily activities and processes.

Understanding Circumstances

For many people, popular culture may be the primary way of understanding, reinforcing, and modifying the circumstances of their lives. Most of the everyday knowledge and experiences that are shared by people (in the form of reading, watching, wearing, using, playing, working, talking, and so forth) make up the concept of popular culture. Popular culture, however, is distinguished from such traditional institutions as education, politics, and religion, although the distinction often becomes hazy. Over time, and with repeated exposure to societal norms (through, for instance, mass media), people form conscious and unconscious impressions of various aspects of life, including attitudes about pollution.

Chronicling the Good Life

Popular culture in the United States and much of the Western world has concentrated on the reoccurring major theme of the search for "the good life."

Social Values, Awareness, and Preferences

As the world's population continues to increase dramatically, and as issues such as global warming, ozone depletion, and the extinction of species garner worldwide attention, popular culture becomes more intertwined with people's environmental beliefs and values. The social values, awareness, and preferences of people are enmeshed in the fundamental moral and religious views between nature and humanity: Is it right to manipulate nature? What is the responsibility of society to future generations? Are the rights of other species more or less important than human rights, or are they equally important? These and many other questions are fundamental to the cultural beliefs and values that guide how people live.

Attitudes about Pollution

Popular culture helps to shape people's general understanding about pollution and the environment. Poll results released in the 1990s have consistently shown that from 50 to 75 percent of all Americans consider themselves to be "environmentalists." Moreover, from extensive survey results analyzed by Riley Dunlap and Rik Scarce, three major conclusions have been made about Americans: (1) they have become much more proenvironment since the 1960s; (2) since the 1980s, their environmentalism extends beyond opinions into their basic values and fundamental beliefs; and (3) their attitude about the environment affects the way they interact, consume, and vote.

Images of Pollution in Popular Culture

Images of the natural environment have been prominent in American popular culture since the ecology movement of the 1970s and 1980s. Music and art focusing on human interaction with the environment became popular beginning in the 1960s. Some popular early images of pollution that are now rooted into popular culture:

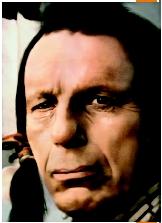

- A public service TV advertisement, which features a Native American with a tear running down his cheek (sometimes called "the crying Indian"). After paddling his canoe up a polluted river with dirty smokestacks crowding the shores, he comes ashore to a littered riverbank only to have more trash tossed carelessly out of a car and land at his feet. The narrator for the Keep America Beautiful television public service advertisement then declared, "People start pollution, people can stop it." (It premiered on the second Earth Day in 1971.)

- The song "Calypso," by John Denver, which was about French explorer and environmentalist Jacques Cousteau's ship, the Calypso. It included the lines "To light up the darkness and show us the way / For though we are strangers in your silent world / To live on the land we must learn from the sea."

- The song "Mercy Mercy Me," by Marvin Gaye, which laments: "Oh mercy mercy me / Oh, things ain't what they used to be no, no / Where did all the blue sky go? / Poison is the wind that blows from the north and south and east."

- The song "Big Yellow Taxi," by Joni Mitchell, released on her 1970 album Ladies of the Canyon. The song's lyrics include, "Don't it always seem to go / That you don't know what you've got 'til it's gone / They paved paradise and put up a parking lot."

- The Smokey the Bear advertisement campaign by the U.S. Forest Service. Over the years (starting in the 1940s), the campaign reminded people: "Remember—Only YOU can prevent forest fires."

- The recycling symbol, with the familiar three colored arrows that represent three recycling-related actions: (1) The red arrow stands for separating recyclables from garbage and recycle them, (2) the blue arrow stands for manufacturing new products from the recyclables, and (3) the green one represents purchasing products made from recycled materials ("green products").

The relationship between popular culture and popular opinion is circular. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the movie business. Hollywood needs good stories and bad guys. Awareness of environmental issues provided it with a wealth of both.

In what was arguably Hollywood's first environmental thriller, life mimicked theater. In The China Syndrome (1979), a TV reporter (played by Jane Fonda) and her cameraman (Michael Douglas) collaborate with a whistle-blower (Jack Lemmon) to expose the risk of a meltdown at a California nuclear power plant. Within weeks of its release, reactor number two at Pennsylvania's Three Mile Island nuclear plant suffered a partial meltdown.

It did not take long for Hollywood to find drama involving real-life whistle-blowers. Silkwood (1983), starring Meryl Streep, Kurt Russell, and Cher, told the story of Karen Silkwood, a chemical technician at the Kerr-McGee plutonium fuels production plant in Crescent, Oklahoma, and a member of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union. Silkwood was an activist critical of plant safety who was inexplicably exposed to plutonium. She was gathering evidence to support her claim that Kerr-McGee was negligent in maintaining plant safety when she was killed in a suspicious one-car crash. The movie was a box-office success; Kerr-McGee settled out of court with Silkwood's family for $1.3 million.

Two later blockbuster movies focused on legal fights against corporate bad guys:

-

A Civil Action

(1999) (based on the book of the same name), starring John Travolta and

Robert Duvall, portrayed the true story of a dedicated—some would

say obsessed—lawyer, Jan Schlichtmann, who took on a case

involving drinking water contaminated by industrial pollution from two

highly regarded corporations, which caused the deaths of innocent

children in Woburn, Massachusetts.

Iron Eyes Cody, the teary-eyed Native American man that was for many years a part of the Keep America Beautiful campaign. (Keep America Beautiful, Inc.)

Iron Eyes Cody, the teary-eyed Native American man that was for many years a part of the Keep America Beautiful campaign. (Keep America Beautiful, Inc.) - Erin Brockovich (2000), starring Julia Roberts and Albert Finney, tells the story of an unlikely real-life heroine, Erin Brockovich, who built a powerful case based on suspicious connections between a powerful electric utility, its abuse of toxic chromium, and the poisoned water supply of Hinkley, California, whose residents had suffered a legacy of death and disease.

Language

The increase in environmental awareness is reflected in the common vernacular: What were once called swamps are now called wetlands; what were once called jungles are now called rain forests; and what was once called a round globe is now called Mother Earth. A shift of perception from insignificant pieces of land to valuable components of an overall ecosystem has shown a fundamental change in cultural awareness. Language, though, is only one example of how a rising awareness of the effects of pollution and a greater understanding of ecosystems has been reflected in U.S. society. An average day contains many small examples of how the environment crisscrosses American lives.

A Typical Day of Enviro-Culture

A day in the life of an average American is filled with popular culture's representations of pollution and the environment. A person makes breakfast with cereal from a company that touts itself as environmentally conscious. Flipping channels while eating breakfast, an individual learns from CNN that an oil spill has occurred overnight near a sensitive coastline, while the Weather Channel reports that beach erosion caused by a hurricane off the coast of North Carolina is harming the natural resources of the sensitive Outer Banks. This average American drives to work in a sport utility vehicle (SUV), which was bought on its ability to drive up rugged mountain roads, but declined to buy a compact car that was advertised to help save the environment because of its fuel economy. This individual arrives in a crowded, concrete parking lot that surrounds a multiple-story office building, as do the other thousands of employees who also drive up singly and sometimes in pairs. The person stops by the grocery store on the way home from work in order to pick up prepared food that has been processed in a factory, but that is heralded as the right way to feed oneself in a wholesome and nutritious manner. And so it goes.

The American individual is exposed daily to images and ideas from popular culture (oftentimes unknowingly) in prepackaged advertisements on television, in newspapers and magazines, on the side of food products, on the Internet, and from hundreds of other sources. Certainly, most people's understanding of pollution issues and policies is formed from such brief tidbits—news reports, literature, and entertainment they encounter throughout their busy day.

American Lore: The Ecology of Images

The use of environmental images in popular culture has figured distinctly in American lore. Included in a paper titled "Ecology of Images," cultural theorist Andrew Ross calls the use of environmental images in popular culture the "ecology of images." The negative images of the natural environment included within the popular culture since the ecology movement emerged in the 1970s have included burning rivers, oil-slick waterfowl, and dirty smokestacks. The positive images include a green planet, rushing, clear waters, and white-peaked mountains. The negative images are often used by activists, who often direct blame onto the industrial sector of the community. The positive images are often shown by the business sector, in an effort to demonstrate how well they get along with nature and the environment. Nature and the environment are used as the means to produce the material goods that are needed and desired in society, but they are often abused as a result of in this materialistic way of living.

Commercialism

Popular culture is a world in which everything is for sale one way or another—a world of commercialism. The environment is often thought of as a product to be consumed, and, as a result, pollution becomes one facet of an ever-growing concern of the American popular culture. Companies involved in the capitalization and industrialization of the United States increasingly promote their products, and themselves, as being in tune with nature.

Greenwashing. D.C. Kinlaw states in Competitive and Green: Sustainable Performance in the Environmental Age, published in 1993, that businesses increasingly associate themselves with nature (sometimes called the "greenwashing" of the environment). Kinlaw continues by saying that only "by making the environment an explicit part of every aspect of the organization's total operation, can the leaders of an organization expect to maintain its competitive position and ensure its survival." By associating themselves with a good environmental policy (even though they may have a poor environmental record), companies can incorporate these advertised ideals into the popular culture for economic gain and for a supposed improvement in the quality of life. Major department stores and name brands promise the "good life" when they advertise a seemingly endless array of clothes, electronics, home furnishings, kitchen appliances, or whatever other material goods they offer. Similarly, Arkansas officials advertise that their state is "the Natural State," Texans can say "Don't Mess with Texas," and Midwesterners can say their states are "America's Breadbasket," but in reality these lands must be used (and often they are environmentally abused) to produce the lumber, oil, wheat, corn, cattle, and pigs necessary to support the economy and economic standards of the United States.

Two Sides of Nature. Nature must be used to fulfill the needs of people, as they endlessly demand new and better products with which to live the good life. Sometimes called "eco-pornography," the pollution that results from manufacturing is not always evident in everyday life, in the blue skies and clear waters of the images seen in popular culture in the form of television commercials, greeting cards, corporate promotions, and in books, magazines, calendars, travelogues, and videos.

The perspective of the environment as a commodity is found throughout the domain of popular culture. The cultural realm shapes and reflects the values, awareness, and preferences concerning pollution. Whether the vehicle is advertising, music, slogans, symbols, or mascots, the power of popular culture to shape society's behaviors and thoughts with respect to pollution is significant.

Bibliography

Anderson, Alison. (1997). Media, Culture, and the Environment. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Dunlap, Riley E.; and Scarce, Rik. (1991). "The Polls—Poll Trends: Environmental Problems and Protection." Public Opinion Quarterly 55:713–734.

Grossberg, Lawrence; Wartella, Ellen; and Whitney, D. Charles. (1998). Media Making: Mass Media in a Popular Culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Kempton, Willett; Boster, James S.; and Hartley, Jennifer A. (1995). Environmental Values in American Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kinlaw, D.C. (1993). Competitive and Green: Sustainable Performance in the Environmental Age. San Diego, CA: Pfeiffer & Company.

Rushkoff, Douglas. (1994). Media Virus! Hidden Agendas in Popular Culture. New York: Ballantine Books.

Ross, Andrew. (1994). The Chicago Gangster Theory of Life: Nature's Debt to Society. New York: Verso.

Internet Resources

America Remembers. "Iron Eyes Cody: The 'Crying Indian.'" Available from http://www.americaremembers.com/FI09100-2.htm .

Dyer, Judith C. "The History of the Recycling Symbol: Gary Anderson, Recycling Dude Extraordinaire." Available from http://home.att.net/~DyerConsequences/recycling_symbol.html .

Earth Odyssey. "Recycling Symbols." Available from http://www.earthodyssey.com/symbols.html .

Federal Trade Commission. "Part 260: Guides for the Use of Environmental Marketing Claims." Available from http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/grnrule/guides980427.htm .

FOX.com "The Simpson's: Official Web Site." Available from http://www.thesimpsons.com .

Keep America Beautiful. "Public Service Announcements." Available from http://www.kab.org/psa1.cfm .

Snopes.com. "Urban Legends Reference Pages: Movies (Iron Eyes Cody)." Urban Legends Reference Pages. Available from http://www.snopes.com/movies/actors/ironeyes.htm .

STLyrics. "Friends—Soundtrack Lyrics (Mitchell, Joni—Big Yellow Taxi [Traffic Jam Mix])."Available from http://www.stlyrics.com/lyrics/friends/bigyellowtaxitrafficjammix.htm .

U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, the National Association of State Foresters, and the Advertising Council. "Smokey's Vault: History of Campaign." Available from http://www.smokeybear.com/vault/history.asp .

Wood, Harold. "Earth Songs." Available from http://www.planetaryexploration.net/patriot/earth_songs.html .

Yamhill County Building and Planning Department, McMinnville, OR. "Yamhill County Solid Waste." Available from http://www.ycsw.org/index.asp .

William Arthur Atkins

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: